Authors: Bill Fienup, mHUB Co-founder and VP of Innovation Services; Jose Cardona, Founder and Principal Engineer at Mechanical Design Labs, Inc.; Jim Shaw, Managing Director, Fastway Engineering; and Matt Mroczek, Chief Strategy Officer, Steel Croissant

There are so many acronyms in the world of engineering, manufacturing, and product development, that the team at mHUB Hardtech Development Services decided to give you an overview of the product development life cycle as well as some of the most important acronyms that many in our ecosystem had to research in our early days as first-time hardtech entrepreneurs. In addition to providing a general overview of the product development lifecycle and some key terms, some links are also shared throughout this post so you can read more in-depth information about each concept. So let’s break it down!

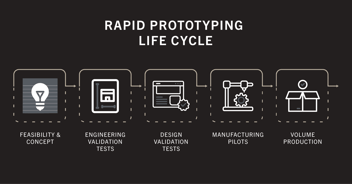

The product development lifecycle is iterative, and has many stages, but essentially starts with POC.

POC stands for Proof of Concept.

When a product developer or hardtech entrepreneur is first starting out, it is important to fully work through product feasibility and general concept. You can plan to utilize HDKs (HDK stands for Hardware Developer Kits), Arduino sensors and/or Raspberry Pi components which are very cost effective and more easily accessible from the marketplace. Concepting the product means sketching out the design, either through drawings or 3D renderings. The overall goal of making a proof of concept is to ideate and mock-up how the product will function / perform. You may have to refine your concept several times before performing EVTs.

EVT stands for Engineering Validation Test.

When you’re at the point where you’re asking “Is my idea possible? Can I prove to others that it works?”, this is when it’s time to conduct an Engineering Validation Test. Moving forward with an Engineering Validation Test enables product developers to do two really important things: (1) identify engineering design fixes needed and (2) determine production intent design. Anna-Katrina Shedletsky does an incredible job of explaining Engineering Validation Tests, Design Validation Tests, and Production Validation Tests in her article on Instrumental1, so it’s highly recommended you read that as she also includes things that can go wrong during these test phases.

After engineering validation tests have been done, then you move on to DVT which incorporates all the design elements – the final form and package.

DVT stands for Design Validation Test.

A Design Validation Test is essentially how a product developer proves that the hardtech they have built actually works for the intended customer the way it has been designed to function. Questions you might ask yourself include: “Does my design fit in the form factor I envisioned? Does it all come together to look like I want?” Form factor means the size, shape, and other physical specifications of components required for your product (inside, outside, throughout). Nico Kruger shares insightful tips for design validation of medical devices that might be of value to startups in the medtech sector.

After conducting design validation tests, then you move to a manufactured pilot (where your prototype is made in the actual materials) in PVT.

PVT stands for Production Validation Test.

Running a Production Validation Test means performing an initial ‘small-batch’ production run, which essentially confirms that the hardtech can be manufactured within your cost projections. With the intention of selling all these initial products to customers, this small production run allows product developers to “verify mass production yields at mass production speeds” 1.

Formlabs published a comprehensive piece on production validation tests, which you know you’re ready for when you start asking: “Are the manufacturing times and costs adequately accounted for? Did any issues come up in quality control when we started manufacturing higher quantities?”

During the manufacturing pilots, hardtech entrepreneurs will manufacture BETA prototypes, complete the tooling design, do test bench validation, and possibly share prototypes with early buyers and/or crowdfunding backers.

As you move into your volume production phases and are thinking about further component and cost optimization, planning new versions, and maybe even thinking about EOL (EOL stands for End of Life – i.e. what you plan to do when it’s time to pull the product from the marketplace, either retiring it altogether, recycling it, or replacing it with the newer, better version), let’s get into some more terms you need to know.

MOQ stands for Minimum Order Quantity.

Minimum Order Quantity is the smallest number of units a hardtech startup is able to order from the manufacturer at a time. When doing a manufacturing run, sometime there is significant material waste purging a machine or long set up costs that involve changing a tool or loading new components. Because of these time and costs, many manufacturers require a certain volume to do a manufacturing run.

MVP stands for Minimum Viable Product.

A Minimum Viable Product is a prototype of your hardtech that attracts the kind of customers that will be early adopters. Having a Minimum Viable Product will enable the hardtech developer to validate the idea earlier in the product development cycle.

Jim Shaw (left) and Corey Davis (right) of Fastway Engineering perform engineering simulation and analysis

PDR stands for Preliminary Design Review.

The purpose of a Preliminary Design Review is to make sure that the design is meeting all the necessary design specifications, or “specs” for short. The audience of the PDR will be all major stakeholders from sales, marketing, advisory/leadership, engineering, manufacturing, etc. A PDR should be conducted before commencing work on the detailed product design. The design will mostly live in a “CAD-only” state, so changes are still easy to make as the design is still mostly digital. Engineering Simulations may have been conducted on the CAD Model to predict performance and reliability, and in some cases, a preliminary 3D-printed prototype has been made as well. Reviewing the conceptual (or “alpha”) design will help the hardtech developer ensure that the planned technical approach is sufficient and will help to resolve major design issues.

CDR stands for Critical Design Review.

The purpose of the Critical Design Review is to make sure the design meets the specs, and is ready for manufacturing. The audience will be all stakeholders from the PDR, plus any manufacturing partners that have been brought on board. At this point numerous prototype iterations have been made, Design For Manufacturing (DFM) considerations have been addressed and the CAD model has been refined into the near-final “beta” design. Typically, engineering simulation has been used to optimize the CAD design, some physical testing has been conducted (and hopefully matches the simulations!), and a Design For Assembly (DFA) assessment will have been conducted so fit and finish can be assessed and manufacturing labor costs can be estimated. In short, Hardtech developers conduct a Critical Design Review to check the detailed design requirements and make sure that the product design can meet its stated performance requirements within projected cost, schedule, and risk.

ECO stands for Engineering Change Order.

Once the product is launched into production, changes may still occur. To ensure that mistakes don’t get overlooked, or to prevent manufacturing tooling from being designed to an outdated spec, Engineering documentation is formally released, and “revision controlled”. This means that it takes a few more eyeballs (and signatures!) to make changes. This is because changes at this point can get really expensive. To keep product development on-track, hardtech startups should utilize Engineering Change Orders as a way to document/specify new product design details or to propose changes to products already in the product development pipeline. Once production starts, engineering is not off the hook yet – as they manage changes by documenting, publishing, and overly communicating them as much as possible!

Jose Cardona, Founder and Principal at Mechanical Design Labs, Inc., working in one of mHUB’s 11 prototyping labs

Now, let’s get into some of the more business, sales, and marketing-minded terms and concepts hardtech entrepreneurs need to know.

Profit Margin Calculator

Not only do you have this fantastic idea for an amazing product that the world needs, but you actually have to make a profitable business. This is where knowing your numbers comes in. Omnicalculator shares some helpful formulas: “The formula for gross margin percentage is as follows: gross_margin = 100 * profit / revenue (when expressed as a percentage). The profit equation is: profit = revenue – costs, so an alternative margin formula is: margin = 100 * (revenue – costs) / revenue. Now that you know how to calculate profit margin, here’s the formula for revenue: revenue = 100 * profit / margin. And finally, to calculate how much you can pay for an item, given your margin and revenue (or profit), do: costs = revenue – margin * revenue / 100”

ROAS stands for Return on Ad Spend.

When your hardtech startup is ready to start marketing its product(s) and you’re considering how much to spend on advertising, it’s good to think about Return On Advertising Spend. ROAS, not ROUS (rodents of unusual size – sorry, we just had to throw a Princess Bride reference in here 😉) is a marketing metric that measures the effectiveness of your digital advertising campaign. Evaluating this metric helps you determine which methods are working and how future advertising efforts can be improved. To calculate ROAS, divide the revenue attributed to your ad campaign by the cost of that campaign. For example, if you spend $1,000 on ads and your revenue is $2k, then ROAS is 200% (2000/1000).

CPM stands for Cost Per Mille.

More digital marketing concepts for you! ‘Cost per mille’ refers to the average amount spent for every thousand times your product ad is loaded by internet browsers. To calculate CPM, divide your ad cost by the number of impressions, and then multiply that total by one thousand. Looking at ad spend helps you figure out which ads are performing better than others so you can re-allocate budget as you go through the ad campaign.

CTR stands for Click Through Rate.

Click Through Rate is the number of clicks that your ad receives divided by the number of times your ad is shown. To calculate this, divide the number of clicks by the number of impressions. For example, if you had 5 clicks and 100 impressions, then your CTR would be 5%.

mHUB Member, Matt Mroczek, Chief Strategy Officer at Steel Croissant, at one of the laser etching workstations

Let’s combine these marketing concepts and think through the following example: A CPM of $10 with a CTR of 2% means that the hardtech entrepreneur paid $10 for twenty people to click on their ad; for a total of $0.50 per ad click. If the product sells for $30, and one of the twenty people buys it, the hardtech entrepreneur spent $10 on ads to make $30 in revenue; for an ROAS of 3. Lastly, if the hardtech entrepreneur’s costs are $15 per product, then their expenses are $10 in ads plus $15 in costs for a $25 total and a profit of $5 on that sale; at a margin of 16.7%.

The team at mHUB hopes these concept overviews and links to other articles will help, and if you are interested in meeting specialists at mHUB Hardtech Development Services who can help your startup on its product development journey, complete the form below!

Follow #mHUBHardtechDev to see the next list of important key terms to know!

References:

1 https://instrumental.com/resources/factory/hardware-engineers-speak-in-code-evt-dvt-pvt-decoded